Connecting at Alliance for Peacebuilding conference

(Washington, DC)-Yesterday, I spoke briefly to two young men in Isfahan, Iran.

No, the Alliance for Peacebuilding (AfP) conference I’m attending hasn’t moved out of DC. Instead, organizers linked us to our new Iranian friends via what they call a portal—a live, head-to-toe video and audio feed.

In our brief encounter, I chatted with two young English-fluent college-age men about Iranian media. The men confirmed what I’d read-that press in Iran is restricted when discussing religion and politics, but relatively free in reporting about other issues. One man said, “We need more spaces for free expression.”

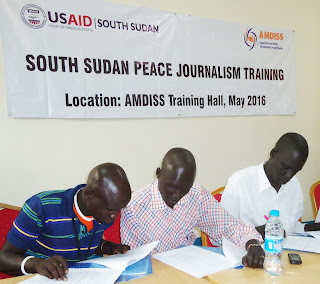

The DC to Iran portal, which is making connections across boundaries, is symbolic of the work being done here this week at AfP by the peacebuilding community. Here, there is agreement about the essential nature of these connections, and about the importance of storytelling, including peace journalism, as a peacebuilding tool.

I spoke about PJ and distorted media narratives at a session on Tuesday. I was joined by a colleague from the American Friends Service committee, Beth Hallowell, who presented an excellent report on media and terrorism. I must admit that it was a nice change to, for once, actually “preach to the choir”—those already committed to peacebuilding.

The AfP conference concluded today with sessions hosted at the U.S. Institute for Peace.

(Washington, DC)-Yesterday, I spoke briefly to two young men in Isfahan, Iran.

|

| Connecting via a portal to Iran |

No, the Alliance for Peacebuilding (AfP) conference I’m attending hasn’t moved out of DC. Instead, organizers linked us to our new Iranian friends via what they call a portal—a live, head-to-toe video and audio feed.

In our brief encounter, I chatted with two young English-fluent college-age men about Iranian media. The men confirmed what I’d read-that press in Iran is restricted when discussing religion and politics, but relatively free in reporting about other issues. One man said, “We need more spaces for free expression.”

The DC to Iran portal, which is making connections across boundaries, is symbolic of the work being done here this week at AfP by the peacebuilding community. Here, there is agreement about the essential nature of these connections, and about the importance of storytelling, including peace journalism, as a peacebuilding tool.

|

| PJ session at AfP |

I spoke about PJ and distorted media narratives at a session on Tuesday. I was joined by a colleague from the American Friends Service committee, Beth Hallowell, who presented an excellent report on media and terrorism. I must admit that it was a nice change to, for once, actually “preach to the choir”—those already committed to peacebuilding.

The AfP conference concluded today with sessions hosted at the U.S. Institute for Peace.